We interviewed Bruno Giannelli in June 2019, who kindly opened the doors of his house in Via Datini. Obviously to repay his kindness in having two strangers in the house who would soon fill him with questions, we armed ourselves with pastries so that the invasion was at least a little sweeter. This section dedicated to Bruno will be a mix between an interview and a story, in order to pass on what he has passed to us, namely the effort and effort, the arrangement, the dirt, the real life of an amateur cyclist of the 1940s.

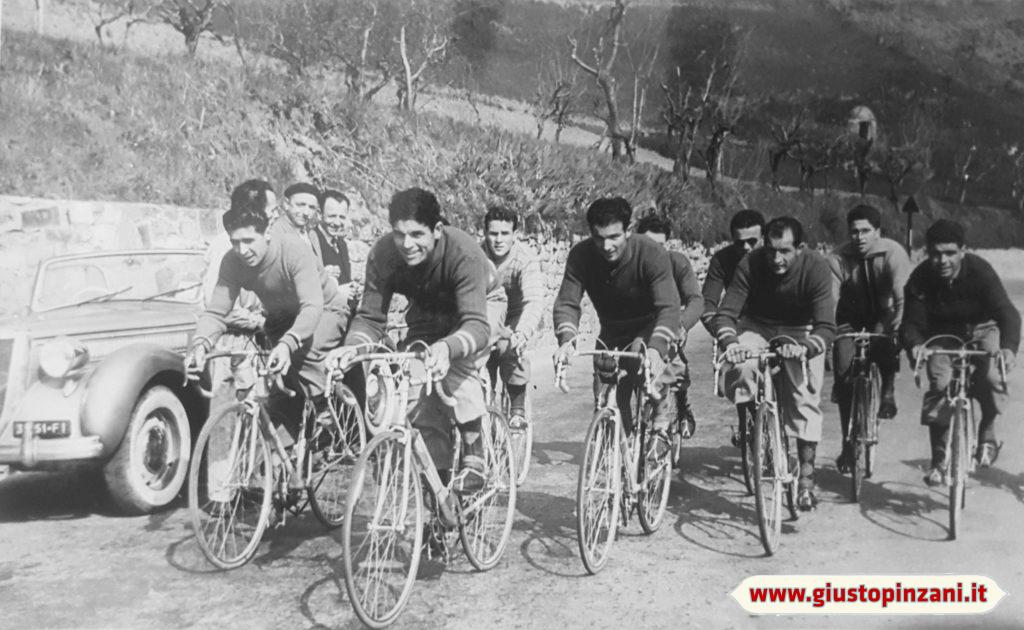

The Florence of those years was very different from today's. The reconstruction of the city from the bombings suffered by the Nazis during the Second World War was underway, but this did not stop the great passion of Florentines and Tuscans, namely cycling. Bartali's sport was dominant over everyone else in those years, leading people on the street to see their idols and to ignite the minds of fans. In Florence there were many sports clubs, such as S.S. Oltrarno, Soffiano, Club Sportivo Florence, Aurora, Assi Rifredi, Porta Romana, Aquila Ponte in Ema, Rifredi, Alfio, Le Cure, Italo Florence, Tavarnuzze and many others. "All teams, built well and better don't believe," Bruno tells us between biscuits. "Cycling in Tuscany usually began in mid-March with the first races organized in Florence. If you were an amateur, you could run almost every day from how many races there were. At each event, about 30 to 70 runners took part and each race contacted the various cycling companies to let them run in their own race, even offering money to have runners in the race. Every now and then it happened that on the same day we of the Oltrarno had to compete in several races, dividing us. Bartolozzi and I always went together, because that's how we knew we were winning."

At that time all the races, both amateur and professional, were organized by the UVI. The UVI, The Italian Velocipedist Union, was born in Pavia in 1885 to regulate on Italian soil all the companies that were born a little throughout the boot. In 1964 it became known as the FCI, the Italian Cycling Federation.

To organize an event you had to contact the UVI, which depending on the investment that the race could afford, managed the whole administrative part for the creation of a race more or less large and therefore more or less rich. Cyclists who participated in the event had to pay a registration fee to cover the cost of the ride, financed the UVI and the rest became the prize pool for the winner. The prizes ranged from 500 lire, going from 800 lire to even further in the races where there were many sponsors.

But how did Bruno Giannelli become a cyclist?

"I liked riding a bike so one day I took it and got a race. And I won it!" In telling us he shows us a picture of him wearing a light camiciolina and a bike that looked more like a walk than a race. Next to the photo is an inscription 1st antella race and a date 3/10/1946. "That race and the free course, what do I mean by free? That there was nothing, no team, no number, nothing. Only the bike and a shirt."

And then he went to the Oltrarno, with the Pinzani bikes. Bruno's answer is one you remember, strong and decisive, even with his 94 years. "Oh look, they did it for me!"

How to blame him, I would have answered so too, it's one of those things you've been bragging about all your life. The Oltrarno Sports Society was born as a wrestling company but soon after was born the cycling section that had immediately great following and had in Bruno obviously the first cyclist.

"After a race at the Antella, who came second, I approached the Pinzani who was following the race and proposed to me to ride his bike. Do you know why people went to the outrage? Because they gave you tubulars! And then they had technical assistance during the races and they took you to Via Gioberti to the shop to repair and clean everything".

After the war, the Italian roads were all dirt and rough and several tubulars were punctured.

They were bought with collections made by the members who at the bar gave a contribution to give them to the cyclists for the next race. In the early years the Oltrarno had quickly reached almost 400 subscribers, so finding a few more pennies was not very difficult.

"At the first race I did not have the official team jersey, but a green shirt with the band on writing Oltrarno sewn by hand in italics by a neighbor, because still the official jerseys had not arrived. Luckily at the time the ward was like a large extended family, otherwise you know what it looks like." Bruno laughs as he uneasks another cookie.

But what was the life of the amateur cyclist back then?

"The start of the races and it was about noon or touch, towards the burned hours to understand. To go to the races you would always start cycling from home and cycling back. I left with a shirt so as not to inseuse the team, I changed leaving the sweaty shirt at the start, I made the run and went home. It was hard. There were no places to wash and bathe. When it was fine there was a fountain where you rinsed your legs and then you row home. For more distant races the team gave us food and lodging. We would ride the bike the day before to stay overnight at the place of the ride."

And with eating like you did? Did you have any supplies along the way?

"Yes, and they gave us a bag of food to eat before the race. Usually chicken, a lot of chicken, a lot of chicken."

As for clothing, that was a company expense. How many animals did they give you each year?

"One!" he cried. Bruno almost rises from the armchair with one hand on the bracelet to support himself while with the other he raises his index finger to reinforce his response. "A shirt and a pair of shorts to wear for all events. After each race they would take and wash. Those of the Tortelli Sisters after a short time that washed down. And if you needed another one, you had to wait until the next year. Pinzani, on the other hand, was a vispo and forward, giving us his jerseys for training, and also the white caps with black Pinzani inscription. The training pants, on the other hand, were normal zuava pants with the socks pulled if they fitted."

Bruno tells us many small anecdotes that describe how cycling had lived in those times.

"In some prestigious races in Florence, such as the Tour of Tuscany, the arrival was put inside the stadium with a lap of athletics track. Once I remember that before the arrival they had organized a Fiorentina game against Sampdoria in order to sit people and entertain them, waiting for our arrival". Or "At these races there were always a lot of people pouring on the streets. Families didn't have television on Sundays, and instead of staying at home they would go out and those who had walking bikes put them in the front row as transennials."

He remembers Bruno, he remembers almost every race he participated in, and pretty much all the races where he won. At one point I ask him what he remembers about the Cremonini Cup. "Tough and crazy, there wasn't a metre of plains," he tells me with a smile, like one who has seen so many but that was one you can't forget. "The owners of Donnini's bodyshop, the Cellai, organized it. In Donnini there was a very hard climb. The race was full of holes, one took off his legs, he always finished the tubulars. I did it twice and a year I had to withdraw for too many punctures."

Bruno, among others, tells us about a lap he usually did with his teammates as a workout on days without race: I meet at 8.00 in front of the old velodrome Pontecchio at the Cascine and return around 4 p.m. From Florence pedaling all over the Valdarno to Montevarchi. Detour on the right to climb towards Castellina, Poggibonzi and Certaldo. I arrive at Castel Fiorentino and from there I go to Pontedera. Another climb to Baths of Lucca and back to Florence." It will have been yes and no 250 – 280 km". Said as if they were few. "And they weren't going for a ride. You were always at all. That climb to the Baths of Lucca, is long up to the Bridge to the Lima…."

Before he became a cyclist Bruno was a plumber. In 1953 he stopped running and abandoned his professionalism, destroyed by having to pick up the crumbs of the three great cyclists of the Italian epic, namely Bartali, Coppi and Magni. She resumed her business from where he left her. After a few years he was directed towards the maintenance of museums and quickly became a maintainer for both the superintendent (Florida museums) and private galleries. He worked for 30 years before retiring.

In the end, the question about Bartali becomes mandatory. Bruno Giannelli was signed by Ginettaccio's team in 1950. "Usually when I wasn't running I was in Via Gavinana, if it was bad weather you would go to the cinema or a club, otherwise I was always at the mechanic there. Bartali often used to go to the store to see his parents. One day he came to my house and asked me if I wanted to run for him, because there was a race for the Giro d'Italia. I had already won some good races and I said yes." This was how Bruno turned professional with the Bartali team and made his way to Milan Sanremo.

At the end of the interview we were galvanized. Bruno had been a remarkable source of news and his vitality had infected us. Some time later, brooding over Gavinana's mechanic, it was natural for us to wonder who it could be. After some research we realized that the answer was obvious, Gavinana and Bartali were clues that gave only one solution: Oscar Casamonti, for all the Florentine Oscare.

He was a good DIY amateur, he already had a bicycle shop in Ponte in Ema, the classic door and shop of the time. And the neighbors were Mr. Bartali. Oscare was a few years older than Gino, but adopted him almost immediately, making him work in his workshop. There are various legends that tell the story of the discovery of the Bartali cyclist. One of them claims that one day Gino went for a bike ride with Oscare and his friends. Determined to pull off everyone, Oscare pushed all the time and in the end the only one left to his wheel was Gino, with a walking bike. From that moment On, Oscar Casamonti was the first to believe in Gino Bartali by entering his first race. Their friendship lasted until their old age with Bartali who always brought some work to his friend, discoverer and mechanic in the workshop of Gavinana.

For the realization of this article I thank

Luciano Fortunati Rossi – tracked down Bruno and accompanied me to the interview

Andrea Martini – he confirmed to me that it was clearly Oscare that mechanic and told me several anecdotes about this great mechanic.

For those who want to delve deeper I recommend two interesting articles written by Lisa Bartali, Gino's granddaughter. One on Bruno Giannelli Here and one on Oscar Casamonti Here